Corky Lee photographs capture a sense of motion as they portray individuals engaged in various activities, whether working, participating in demonstrations, or leaving their mark on significant historical moments.

Corky (Young Kwok) Lee, a Chinese American photographer, spent more than four decades documenting Asian American culture and history. Tragically, he passed away in late January due to Covid-19-related complications.

He proudly referred to himself as the “unofficial Asian American photographer laureate” and viewed his work as a humble effort to address the historical omissions present in textbooks.

Born in Queens, New York City, Corky Lee was the second child of Chinese immigrant parents. His mother worked as a seamstress, while his father, a World War II veteran and former welder, established a hand-laundry business.

His interest in photojournalism was sparked during junior high school when he found a famous picture in a history textbook. The image depicted two trains meeting at Promontory Point, Utah, to celebrate the transcontinental railroad’s completion in 1869.

The women emphasize that their stories have often been told by people other than themselves

However, what struck him deeply was the absence of Chinese faces in that photograph, even though thousands of Chinese laborers had sacrificed their lives while constructing the most dangerous segments of the railway.

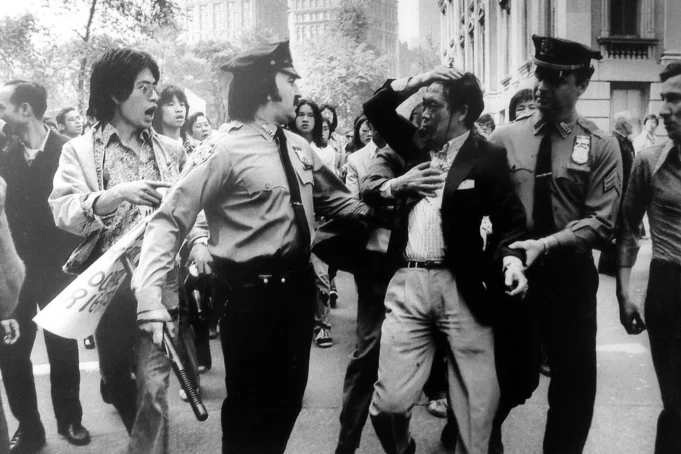

Lee self-taught photography, initially borrowing cameras from friends. He established a regular presence at festivals and protests in New York Chinatown. In 1975, he captured a powerful moment when he photographed Peter Yew, a Chinese American man who had been subjected to assault by New York City Police Department members after he intervened to stop them from beating a teenager for a traffic violation. The photograph made its way to the front page of the New York Post the following day.

Also, he extended his photographic endeavours beyond New York, documenting protests in Detroit following the 1982 murder of Chinese American Vincent Chin. In 2014, he recreated the iconic Promontory Point photograph featuring the American-born descendants of Chinese railroad workers.

Lee has made his works public through publications in newspapers and periodicals, as well as showcasing them in various art venues like the Overseas Chinese History Museum of China in Beijing, the Museum of Chinese in the Americas in New York, the Chinese American Museum in Los Angeles, and the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

The photographic series named “Asian Women in America” presented images of Asian American women engaged in various professional settings, including sitting in offices, working in medical labs, and contributing to their communities.

Alongside these Corky Lee photos, short first-person narratives accompany a diverse group of women, including a New York taxi driver, a medical student in New Orleans, a minister within the New York City Korean American community, and the director of the New York City Jazz Coalition.

In these narratives, they recount instances where others have questioned their professional identity and discouraged them from pursuing their chosen career paths.

The women stress that their stories have usually been narrated by individuals other than themselves.

Lee’s legacy will be etched in memory for capturing and documenting significant moments in Asian American culture and history over the last five decades, right up until the months before his passing.

In October of the previous year, he curated an exhibition at a newsstand situated in New York’s Chinatown. The showcased photographs portrayed local residents and visitors set against the backdrop of historical buildings within the neighbourhood.

Shortly after the Christmas season, he captured photographs of members from the Guardian Angels organization stationed at various New York subway stations. The images showed them distributing flyers that cautioned against violence during the Covid-19 pandemic targeted at Asian Americans.

In China, there was minimal news coverage of Lee’s passing. Nevertheless, the Overseas Chinese History Museum of China features two of his photographs in its permanent exhibition.

These pictures capture the protests against police brutality in 1975 and a rally in New York during the same year, where Chinese Americans advocated for access to taxi services and the right to celebrate Chinese New Year.

Lee generously donated eight of his artworks to the museum and graced the opening ceremony in Beijing in 2014. A mutual acquaintance based in New York introduced him to the curators.

Within New York’s Chinatown, Lee was a mentor and played a significant role in connecting artists and community members. In February, during an online tribute organized by the Asian American Arts Alliance, artists fondly recalled Lee’s pivotal position in the New York Asian American community.

Photographer Alan Chin described Lee’s purposeful mission to capture the community through photography, attending every community event with unwavering dedication. Chin emphasized that Lee proactively created this role for himself, rising to the occasion to intentionally document the community’s moments.

An Rong Xu, speaking from Taipei, was deeply moved by Lee’s commitment to making sure that individuals in the community felt valued and would be remembered. As a poignant example, Lee had taken a photograph of Xu when he was an elementary school student, exemplifying his dedication to capturing and preserving the stories of community members.

Years later, while residing in New York as a photographer, Xu encountered Lee again. Although Xu had long forgotten their initial meeting decades ago, Lee still vividly remembered it. To Xu’s surprise, Lee later shared the photograph he had taken of him as a child, showcasing his remarkable memory and dedication to cherishing such moments.

As racism and attacks targeting Chinese and Asians escalate worldwide, it becomes increasingly crucial for Asian Americans to envision themselves as integral parts of the broader tapestry of American history.

Lee’s photographs go beyond capturing pivotal moments; they also celebrate everyday community cultural events, such as Chinese New Year and Fourth of July parades. His diverse portfolio even includes shots of Sonya Thomas, a Korean woman who achieved multiple victories in the Coney Island hot dog eating contest.

For people belonging to visible minorities, the perception of oneself is closely tied to how others perceive them. Images play an important role in helping us visualize the communities we are part of and where we can position ourselves within significant historical narratives.

Through Lee’s photographs, the personal stories and public history of Chinese American communities were made visible to a broader audience and contributed to shaping a collective vision of a united community with shared history, common objectives, and political influence. This social context gave Chinese Americans a way to perceive themselves within a cohesive and empowered framework.

Check Out: Remembering Corky Lee Photos- Picture-Perfect Weddings: How Wedding Websites Enhance Your Invitations With Stunning Templates

- Remembering Corky Lee Photos

- Download Here 5120x1440p 329 Helicopters Images!